Federal Budget 2024-25 reflections

Reflections on the 2024-25 Federal Budget

Treasurer Jim Chalmers led with cost-of-living relief and inflation control as the centrepiece of this year’s Federal budget, along with investment in new housing, infrastructure, and decarbonisation initiatives. There are certainly some important commitments to drive economic growth and navigate Australia’s net zero transition. But the jury’s out on whether the budget measures will mitigate underlying inflationary pressures, at least in the short term.

Budget finances

The budget bottom line is projected to move from a surplus of $9.3 billion in 2023-24 to deficits of $28.3 billion in 2024-25 and $42.8 billion in 2025-26. This is partly driven by the government’s infrastructure investment program and the Future Made in Australia initiative, but the cost-of-living supports payments and Stage 3 tax cuts are also contributing to these deficits. In a real sense, the Government is picking up the tab for the high inflation we’ve faced over the past two years.

The ‘golden rule’ of public finance suggests that governments should follow a balanced budget over the course of an economic cycle, and to borrow to invest in productive capital and expand the economy. Some of the Treasurer’s commitments over the next three years are consistent with this goal, particularly infrastructure projects and decarbonisation initiatives, and potentially the Future Made In Australia program as long as it is targeted effectively.

Additional resourcing for Services Australia is clearly necessary to fund the extra work needed to deal with the impact of cost-of-living pressures on many Australian families. But the government needs to be careful not to embed this recurrent spending into a structural deficit.

Cost of living measures and inflation control

Alongside energy cost rebates worth $325 to around 1 million small businesses, the $300 energy bill relief payment goes to every Australian household with power bills, regardless of their incomes. However, we know that families on the lowest incomes have been hardest hit from the cumulative impact of rising costs of living and a far greater share of their spending goes towards food, energy, and housing costs. The energy bill payment will be a welcome contribution to the cost-of-living pressures faced by financially vulnerable households, but it’s a one-off payment that doesn’t go anywhere near the accumulated costs people have borne over at least two years. Bear in mind that median rental costs have risen by $2,700 over the past year alone.

The energy bill relief payments and extra Commonwealth Rent Assistance will technically reduce CPI, but only in a mechanical sense. The payments don’t reduce the prices being charged for energy, or the rents being charged for accommodation. Instead, the government is contributing towards the accumulated cost of living pressures that families and businesses have been facing for more than two years because of price inflation. Without the government weighing in with direct cost-of-living support to families, next year’s CPI growth would be a lot higher and likely much closer to the Reserve Bank’s 3.8 per cent figure.

Price and wages growth

Consumer price inflation is expected to hit 3.5 per cent by the end of this year and drop to 2.75 per cent from 2024-25, bringing inflation back into the RBA’s target band. With actual CPI growth at 3.6 per cent on the latest ABS price data, the 2023-24 estimate in this year’s budget is pretty much guaranteed. But as I’ve said, next year’s inflation forecast of 2.75 per cent borrows heavily from the energy bill relief and extra rental support.

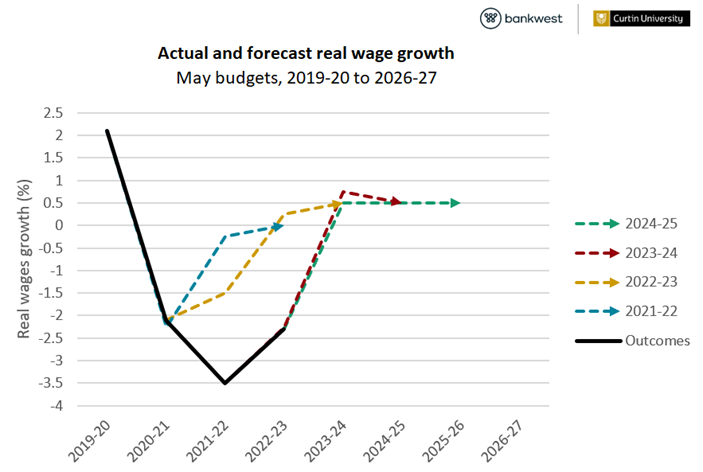

Wages are expected to grow by an estimated 4 per cent in 2023-24 with a slower growth rate of 3.25 per cent in later years. Taken in combination, these wage and price inflation figures combine into projected real wage growth of 0.5 per cent from 2023-24 onwards. Families will be able to recover the lost purchasing power of their wages if these outcomes eventuate, but only very slowly. Given how hard families have been hit by the cumulative impact of rising prices over the past two years and more, it will take far longer – certainly late into this decade – for the real value of wages to get back to where they were at the start of the decade.

When is a tax cut not a tax cut?

The government confirmed its deployment of the modified Stage 3 tax reforms from 1 July 2024, but the justification seems to vary depending on where you look in the budget papers. The reforms are styled as ‘tax cuts’ to counter cost-of-living pressures in some places. But in other places, Stage 3 is promoted by the government as a response to bracket creep – the line of argument used by the Coalition as the original architects of the Personal Income Tax Reform plan.

There’s no doubt that lower personal tax liabilities will be welcomed by taxpayers. But are they really tax cuts intended to provide cost-of-living relief? Or is the government returning to families the tax increases that they have endured as a result of growth in prices and wages.

If personal taxation thresholds were indexed, for example to the lower of wage and price inflation, then we wouldn’t be having this issue. Indexation would neutralise the tax system and protect average tax burdens from rising with inflation – this is the default in many countries, for example in the United Kingdom.

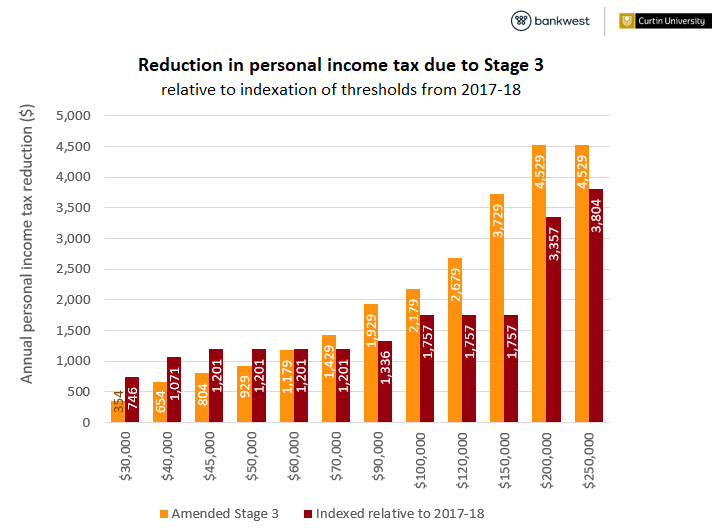

And what’s less appreciated is that the modifications introduced by the Labor government still overcompensate middle- and higher income earners and undercompensate those on low incomes when we compare Stage 3 to a system where thresholds have been indexed from 2018-19.

I appreciate that the Low- and Middle-Income Tax Offset provided extra financial support to lower earning families, but it ended two years ago and doesn’t help people now. If the Stage 3 reforms have been designed as a response to bracket creep, they’ve fallen a little short of the target.

Proponents of non-indexation put forward a long-held, institutionalised defence that by not lifting thresholds in line with either prices or wages, the higher average tax revenues help to cool the economy when it’s running too hot – what macroeconomists call an ‘automatic stabiliser’.

But this seems a bit of a non sequitur, given that you get bracket creep (and rising average tax burdens) whenever nominal wages grow, regardless of how fast consumer prices are rising.

If non-indexation is considered as some sort of tiller that stabilises the economy, then it’s definitely listing in favour of the government.

And finally…

And the prize for the greatest contortion in budget commentary has to go to The Australian. They tag high income earners as losers in this year’s budget despite them being over $4,500 better off next year as a result of the Stage 3 tax reforms, because the benefits are less than would have been the case if the original measure put forward by the former Coalition government had been retained. Not sure about that…

Professor Alan Duncan is Director of the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre.