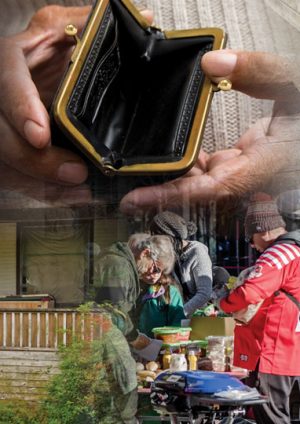

JobSeeker and Commonwealth Rent Assistance reform urgently needed to lift up to 1 million Australians out of severe poverty

— High rental costs leave many with less than $150 per week after housing costs –

— 11.8 per cent of population including nearly 750,000 children live in poverty –

— One in five people living in poverty are in low paid employment —

Released today by the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, the ‘Behind the Line: Poverty and disadvantage in Australia 2022’ report has revealed the COVID-19 pandemic has forced housing costs to unmanageable levels, leaving many people struggling to cover other living expenses such as food and household bills.

Author and Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre Director John Curtin Distinguished Professor Alan Duncan said high rental costs had increased poverty among private sector renters, 1.5 million of whom in Australia are living in poverty, with the poorest families left with less than $150 per week once housing costs have been paid.

“Private rental costs have risen so significantly over the past two years, that further increases in rent would be financially catastrophic for up to 1 million Australians living in severe poverty,” Professor Duncan said.

“Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) is capped at $142.80 per fortnight once rents reach $318 per fortnight and with minimum rents of at least $300 per week in many parts of Australia, the maximum CRA payment is no longer adequate, covering less than a quarter of the rent of most recipients.

“The CRA provides no protection against further rent rises once the maximum CRA payment is reached, which means every extra dollar a person is charged in rent is one less dollar to spend on things such as food and bills.

“When combined, JobSeeker and CRA payments total $386.15 a week, which is woefully inadequate as a protection against rising costs of living for many recipients. Even if recipients can find rental accommodation at the budget price of $250 per week, this leaves only $136 per week to live on.”

Professor Duncan said the COVID pandemic had provided a stress test for government support systems for people on low incomes or in poverty and had found these systems to be severely inadequate and in need of rectification.

“Modelling in the report projected that relatively small increases to both the JobSeeker rate and Commonwealth Rent Assistance would go a long way towards reducing severe poverty in Australia,” Professor Duncan said.

“An increase of 30 percent in the CRA maximum payment along with a $140 per week increase in the base JobSeeker rate and related payments would protect up to 1 million people from rising rents and high costs of living, and would be a huge step in tackling the poverty crisis.”

The report also found social housing to be one of the most important levers at the disposal of state and territory governments in the fight against poverty.

“Social housing has never been more important as a way to provide secure, affordable homes to those in deepest financial hardship,” Professor Duncan said.

“Our findings show the poverty rate for social housing tenants reduced by 6.7 percentage points since the start of the COVID pandemic.”

The report is based on data from the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. The latest release of HILDA data covers the period from August 2020 to February 2021 and is among the most recent representative population data that takes in the COVID-19 period.

Key findings:

POVERTY DEPTH

- The poorest couples in Australia survive on less than $270 per week.

- Nearly one million Australians – around 5.8 per cent of the population – are living in severe income poverty with incomes below 30 per cent of the national median income after housing costs.

- Of the 750,000 children living in poverty, over 190,000 are experiencing severe poverty.

- Over a quarter of single parents are in poverty, with one in ten experiencing severe poverty.

- Poverty is more pronounced for women than men, with larger gender differences in rates of poverty for young women and women aged 55 and over.

HOUSING

- High rental costs have increased poverty among renters.

- 1.5 million renters in Australia are in poverty, with the poorest families left with no more than $150 per week after housing costs are paid.

- The maximum Commonwealth rent assistance is $71.40 per week, compared to private sector rents of at least $300.

- Rental costs have increased over the last five years by $100 per week in Canberra and by at least $50 per week in Sydney, Adelaide and Perth.

- The maximum rate of rent assistance has increased by $6.10 per week over five years.

- 53.8 per cent of people who rent from a government housing authority are in poverty.

- The poverty rate for people in social housing has fallen by 6.7 percentage points over the last two years.

UNEMPLOYMENT

- Joblessness is a key driver of poverty, particularly for single people and people living in large families.

- Nearly two thirds of single jobless people and 55 per cent of single parents without jobs have incomes below the ‘standard’ poverty line.

- JobSeeker payments are currently $388.35 per week including rent assistance and the energy supplement.

- Around 105,000 unemployed people are in severe poverty in Australia.

- An increase of $25 per day in the JobSeeker base rate combined with $30 per week extra in rent assistance would virtually eliminate severe poverty in Australia.

A LIFETIME OF HARDSHIP

- Persistent poverty is shown to be damaging to health and wellbeing.

- 575,000 people have been in poverty for at least five of the last ten years.

- 330,000 single people and 250,000 single parents have been in poverty for at least five of the last ten years.

- 115,000 people have experienced financial hardship consistently for a decade or more.

- People in poverty for at least five of the last ten years are 3 times more likely to suffer acute mental stress compared to people who are never in poverty.

- The psychological trauma from persistent poverty rises more steeply for women than for men in most age groups.

EMPLOYMENT

- One in five people in poverty are in low paid employment.

- One in eight agriculture workers and 10 per cent of workers in accommodation and food services have earnings below the poverty line.

- Poverty rates fell by 6 percentage points among casual workers who remained in employment during COVID-19.

- There were 220,000 fewer casual workers in 2020 than 2019.

- Poverty rates for casual workers dropped between 2019 and 2020 by a far greater margin for workers in organisations that were able to claim the JobKeeper payment.

- Poverty rates dropped to 9.4 per cent in 2020 for casual workers in organisations where no JobKeeper payments were claimed, but to 5.6 per cent for workers in companies that claimed JobKeeper.

- Average weekly earnings for casual workers rose from $616 per week in 2019 to $754 per week when their employers were able to claim JobKeeper, but to only $650 per week when this was not the case.

CHILDHOOD POVERTY

- Poverty scars children and affects their economic, social and health outcomes in adulthood.

- People who come from a poor family experience inferior economic outcomes and poorer mental and psychological health.

- People who experience childhood poverty are up to 8 percentage points more likely to remain in poverty in adult life.

- The probability of employment is up to 11 percentage points lower for children who experienced poverty in childhood compared to those who did not come from a poor childhood background.

- Young adults who experienced poverty in childhood are significantly more likely to suffer from nervousness or feel unhappy with their lives for up to 10 years after leaving home.

- Targeted strategies to reduce poverty will deliver economic returns, and positive social, psychological and health benefits.